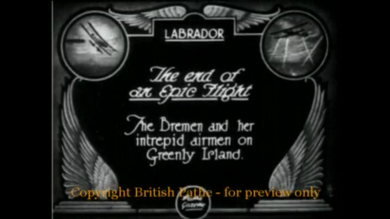

Greenly Diaries 1784 - 1838 (Lady Elzabe[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [13.3 MB]

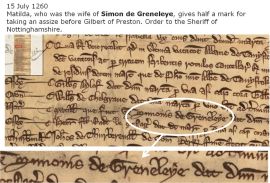

THE RECORDS OF THE SOCIETY OF GENTLEMEN PRACTISERS IN THE COURTS OF

LAW AND EQUITY CALLED THE LAW SOCIETY (1738 – 1810).

The following are minutes from an early meeting of the ‘Society of Gentleman Practisers’ later to become the Law Society. The meeting wasd monthly and took place at Mr William Greenly’s tavern the ‘Crown and Rolls Tavern’ in Chancery Lane, London. This area is still the legal heart of London.

Mr William Greenly was from Hereford in Herefordshire. He also used to host the meeting of the Herefordshire Society, for significant sons of Herefordshire that were in London at that time.

Mr Greenly was trusted with the safe keeping of a trunk which held all of the Law Societies papers and books.

SOCIETY OF GENTLEMEN PRACTISERS.

" Mr. Bowman again submits it to Mr. Pardoe if it wd not be proper to call a Committee of the Law Society forthwith, pursuant to the order made at the last Genl. Meeting, as the time for the Society's next meeting is now near at hand.

Jan. 31, 1786."

Under the above is written: "Feb. !st. Left the original with Mr.

Greenly to be given to Mr. Pardoe."

The following appears to be the rough draft of a letter, as it contains several alterations and erasures :

"Sir,

At the last Genl Meetg of the' Law Society the Trunk containing the

books and papers belonging to the Society were directed to be left in Mr. Greenly's custody, where they now remain. Mr. Windus has the money

collected on that day. The Secretary reed the following direction : ' The Committee with the late Stewards to be summoned for the i8th July at 2 in the afternoon at Mr. Greenly's, the Comittee to be an open Committee.'

The Secretary accordingly summoned the whole Committee and the late

Stewards, when Messrs. Hodges & Skirrow of the Committee & Messrs.

Windus (one of the late Stewards) and Estcourt only attend g, they adjourned the business of the Meeting sine die till there was an opportunity of a more full attendance. I am therefore requested to know when it will be proper to summon another Committee as it is now the time of making out the books &c. previous to the next Genl Meetg.

" I am, &c.

E. B. Secretary.

"Monday, Deer. 5, 1785.

Mr. Pardoe.

Left a copy hereof under seal at Mr. Greenly's, die dat. W. B.

12 Dec. Left a like copy for Mr. Fothergill with his servant. W. B."

" At a meeting of the Comittee at Mr. Greenly's, the Crown and Rolls Tavern in Chancery Lane, on Monday the i8th day of July, 1785. Present : —

Mr. Hodges, ) ^^ ^j^^ Committee.

Mr. Skirrow, )

Mr. Windus, one of the Stewards.

Mr. Estcourt, a member,

and after waiting a considerable time and there not being a sufficient number present, they adjourned the Committee sine die next Term. Mr. Greenly is to keep the box in the meantime.

After the breaking up of the meetg I called on Mr. Cecil, he not being at home left word of the Adjournment. W. B."

Edward Greenly _ His Majestys Proctor Ge[...]

Adobe Acrobat document [411.8 KB]

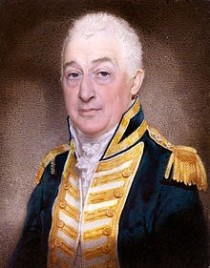

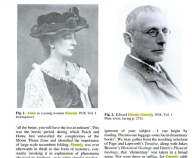

Edward Greenly, of Titley Court, His Majesty’s Procurator General

(1680 – 1750)

1. Edward Richard Greenly, King's Proctor General, was a descendant of

(John Greenlye of Titley Court, Andrew Of Tyttley, Edward Greenelye of Tyttelye, John Greneleye Of Moldeley, Richard Grenelye, Philip the elder of Moldeley, John of Moldely, Phillip Greneley of Moldely, William Grenelye),

Edward was the son of John and Phoebe (Hyde) Greenlye, he was born in April

1680 in Titley, Herefordshire, England and died in 1750 at Doctors

Common, London. Doctors Common being the place where senior lawyers worked in London.

Edward married on 3 April 1725 at St. Anne's Soho, Westminster, London, to Mary Shepherd, who was born in September 1677 at Westminster, London and died on 15 August 1777 in Kingston Upon Thames?, she was the daughter of Henry and Alice (Unknown Surname) Shepherd.

Edward was baptized on 23 April 1680 in Titley. Edward became the King's

Proctor General (Head Lawyer), the leading law officer to the Crown and was extremely wealthy in his own right. He lived in London (close to Doctors Common),

and at Norbiton Hall, Kingston upon Thames, the family seat of his wife, Mary Shepherd.

Norbiton Hall, Surrey.

Children of Edward and Mary (Shepherd) Greenly:

i. Mary Greenly, b. in June 1726. Mary was baptized on 10 June 1726 at St. Andrews, Holborn, London, ENG.

ii. John Greenly, b. in February 1730/31; married 29 July 1764 at St. Clement Danes, Westminster, London, ENG, Ann Port. Ann was born about 1733. John was baptized on 24 February 1730/31 at St. Clement Danes.

iii. Edward Greenly, b. in October 1733; d. 23 March 1733/34.

Edward was baptized on 29 October 1733 in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, ENG.

iv. Edward Greenly of Norbiton Hall, b. in December 1735; d.

19 June 1793; married about 1756, Elizabeth Greenly. Elizabeth was born in August 1734 in Titley and died on 18 March 1808.

v. Elizabeth Greenly, b. in April 1737; married 23 December 1777 in Thames Ditton, Surrey, England, Christopher Lake-Moody LL.D. Christopher was born on 8 February 1754. Elizabeth was baptized on 24 April 1737 in Kingston upon Thames. She participated in a Publication

of 'Poetic Trifles', first volume of poetry in 1798 in London.

vi. Anne Greenly, b. in December 1738; married Peregrine

Fyrge. Anne was baptized on 17 December 1738 in Kingston upon Thames.

vii. Charlotte Greenly, b. about 1740; married Edmund Bull.

Second Generation

Norbiton Hall, Surrey.

Edward Greenly of Norbiton Hall, Descendants, (Edward Richard Greenly, King's Proctor, John Greenlye of Titley Court, Andrew Of Tyttley, Edward Greenelye of Tyttelye, John Greneleye Of Moldeley, Richard Grenelye, Philip the elder of Moldeley, John of Moldely, Phillip Greneley of Moldely, William Grenelye),

son of Edward Richard and Greenly and Mary (Shepherd) Greenly, was born in December 1735 and died on 19 June 1793. He married his cousin about 1756, Elizabeth Greenly, who was born in August 1734 in Titley, Herefordshire, England and died on 18 March 1808, daughter of John and Elizabeth (Boutcher) Greenly.

Edward was baptized on 21 December 1735 in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, ENG.

Children of Edward and Elizabeth (cousin Greenly) Greenly:

i. Edward Greenly, b. about 1755; d. in 1823.

ii. Elizabeth Greenly, b. in March 1756; d. in 1841; married 2 December 1768 in Richmond, Surrey, England, James Morton. James was born about 1755. Elizabeth was baptized on 2 March 1756 in

Ludlow, Shropshire, ENG.

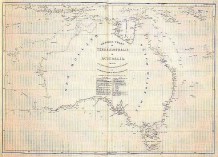

Edward Greenly, the famous Geologist, was born in Bristol 1861 and died 1951. He was married to Annie and they are both buried on the Isle of Anglesey. In his own words, “ was diverted from a career in law towards geology..”. I assume there is a link between this Edward and the previous generations that had all been connected to careers in law. I have, as yet, to find that link.

There follows a nice article by none other than Charles Dickens where he describes a chance visit to Doctor’s Common.

Victorian London - Legal System - Courts - Doctors' Commons by Charles Dickens 1836

Walking without any definite object through St. Paul's Churchyard, a little while ago, we happened to turn down a street entitled 'Paul's-chain,' and keeping straight forward for a few hundred yards, found ourself, as a natural consequence, in Doctors' Commons.

Now Doctors' Commons being familiar by name to everybody, as the place where they grant marriage-licenses to love-sick couples, and divorces to unfaithful ones; register the wills of people who have any property to leave, and punish hasty gentlemen who call ladies by unpleasant names, we no sooner discovered that we were really within its precincts, than we felt a laudable desire to become better acquainted therewith; and as the first object of our curiosity was the Court, whose decrees can even unloose the bonds of matrimony, we procured a direction to it; and bent our steps thither without delay.

Crossing a quiet and shady court-yard, paved with stone, and frowned upon by old red brick houses, on the doors of which were painted the names of sundry learned civilians, we paused before a small, green-baized, brass-headed-nailed door, which yielding to our gentle push, at once admitted us into an old quaint-looking apartment, with sunken windows, and black carved wainscoting, at the upper end of which, seated on a raised platform, of semicircular shape, were about a dozen solemn-looking gentlemen, in crimson gowns and wigs.

At a more elevated desk in the centre, sat a very fat and red-faced gentleman, in tortoise-shell spectacles, whose dignified appearance announced the judge; and round a long green-baized table below, something like a billiard-table without the cushions and pockets, were a number of very self-important-looking personages, in stiff neckcloths, and black gowns with white fur collars, whom we at once set down as proctors.

At the lower end of the billiard-table was an individual in an arm-chair, and a wig, whom we afterwards discovered to be the registrar; and seated behind a little desk, near the door, were a respectable-looking man in black, of about twenty-stone weight or thereabouts, and a fat-faced, smirking, civil-looking body, in a black gown, black kid gloves, knee shorts, and silks, with a shirt-frill in his bosom, curls on his head, and a silver staff in his hand, whom we had no difficulty in recognising as the officer of the Court.

The latter, indeed, speedily set our mind at rest upon this point, for, advancing to our elbow, and opening a conversation forthwith, he had communicated to us, in less than five minutes, that he was the apparitor, and the other the court-keeper; that this was the Arches Court, and therefore the counsel wore red gowns, and the proctors fur collars; and that when the other Courts sat there, they didn't wear red gowns or fur collars either; with many other scraps of intelligence equally interesting. Besides these two officers, there was a little thin old man, with long grizzly hair, crouched in a remote corner, whose duty, our communicative friend informed us, was to ring a large hand-bell when the Court opened in the morning, and who, for aught his appearance betokened to the contrary, might have been similarly employed for the last two centuries at least.

The red-faced gentleman in the tortoise-shell spectacles had got all the talk to himself just then, and very well he was doing it, too, only he spoke very fast, but that was habit; and rather thick, but that was good living. So we had plenty of time to look about us. There was one individual who amused us mightily. This was one of the bewigged gentlemen in the red robes, who was straddling before the fire in the centre of the Court, in the attitude of the brazen Colossus, to the complete exclusion of everybody else. He had gathered up his robe behind, in much the same manner as a slovenly woman would her petticoats on a very dirty day, in order that he might feel the full warmth of the fire. His wig was put on all awry, with the tail straggling about his neck; his scanty grey trousers and short black gaiters, made in the worst possible style, imported an additional inelegant appearance to his uncouth person; and his limp, badly-starched shirt-collar almost obscured his eyes. We shall never be able to claim any credit as a physiognomist again, for, after a careful scrutiny of this gentleman's countenance, we had come to the conclusion that it bespoke nothing but conceit and silliness, when our friend with the silver staff whispered in our ear that he was no other than a doctor of civil law, and heaven knows what besides.

So of course we were mistaken, and he must be a very talented man. He conceals it so well though - perhaps with the merciful view of not astonishing ordinary people too much - that you would

suppose him to be one of the stupidest dogs alive.

The gentleman in the spectacles having concluded his judgment, and a few minutes having been allowed to elapse, to afford time for the buzz of the Court to subside, the registrar

called on the next cause, which was 'the office of the Judge promoted by Bumple against Sludberry.' A general movement was visible in the Court, at this announcement, and the obliging functionary

with silver staff whispered us that 'there would be some fun now, for this was a brawling case.'

Charles Dickens, 1836

Abraham Lincoln wrote to Horace Greenly

Lincoln was raised by a poor family; he worked hard and educated himself. He formed his own opinions and morals based largely on his own self-education. Through his presidency, Lincoln changed his stance on slavery, leading to the eventual emancipation and freedom of slaves. Lincoln will always be remembered for the positive impact he had on the history of the United States of America.

A Simple Man and His Country

Lincoln is considered one of the greatest presidents the United States has ever had. Lincoln was not only a man of great citizenship, but through his presidency he proved he was a man of great moral ethics. His ethics were especially apparent with his views on slavery and how these views changed through his political career. Lincoln, unlike many others who rise to power throughout the world was born in a humble setting. He educated himself and had a huge desire to learn. Coming from humble beginnings Lincoln knew what it was like to be an average citizen. When he became president, he maintained his ethics with the goal of making positive changes, such as abolishing slavery, for the United States. These are ethics that were instilled in Lincoln from his family from a young age.

Lincoln was born into a poor family. His parents were both illiterate which was typical during that time. When Lincoln was young he worked on the farm with his father. If one had looked at Lincoln in this time period they would think, “He will be on a farm for the rest of his life.” Most who worked on farms never got off them. However, he always found time to read. After work and while he was on break he would read books over and over again. This reading and drive to learn showed that Lincoln would be capable of forming his own opinions and ethics rather than gathering them from other people. Forming his own opinions kept him from reacting to the propaganda and advice fed to all, especially in the time he spent as a member of Congress.

In a letter written to Joshua F. Speed, a friend with pro-slavery views, Lincoln stated, “You may remember . . . -there were on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio River or any other slave border” (Lincoln, 21). This statement shows Lincolns personal disgust with slavery. Speed was an old friend of Lincoln; he held slaves and a different opinion than Lincoln. Lincoln had respect for those who had a different opinion than his. This is an example of how his ethics showed through. When one can respect the opinion of others and maintain their own opinions of morality it is a sign of a great man. Though Lincoln did not think slavery was right for moral reasons, he did not think it was the federal governments place to say whether slavery should have been legal or not.

In Lincolns 1857 speech on the Dred Scott decision he states near the end, “Let us be brought to believe it is morally right, and, at the same time, favorable to, or at least, not against our interest, to transfer the African to his native clime” (Lincoln, 29). Today the idea of shipping all the black people to Africa sounds completely ridiculous. In a Pre-Civil War America, this was actually somewhat progressive because it departed from the view that slavery was an acceptable practice. Lincoln’s statement was progressive for the time and showed that his morals were slowly starting change his regarding the issue of slavery.

Moving into Lincolns run for president, he kept the platform that he would not touch slavery where it already existed but he would stop its spread to the best of his ability. In a personal letter that Lincoln wrote to John A. Gilmer Lincoln said, “Is it desired that I shall shift the ground upon which I have been elected? I can not do it” (Lincoln, 60). Five days later Lincoln stated his exact views in a personal letter to Alexander H. Stephens by saying, “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted” (Lincoln, 62). Here Lincoln is expressing his feelings about slavery. In the following sentence, Lincoln states, “That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only difference between us (Lincoln, 62). This shows Lincoln had the ability to be friends and respect a man with different opinion.

Until 1862, Lincoln’s personal thoughts about the wickedness of slavery were held back by his strong belief in the institution of American democracy. On March 6, 1862, Lincoln presented legislation to Congress that introduced the idea of a slow, compensated emancipation. Congress approved this several weeks later. This showed that congress was on board with Lincoln’s personal views that slavery needed to be abolished. On April 16th, six days after congress’s vote, slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia and funds were provided to compensate past slave owners. This was the start of Lincolns plan for gradual emancipation (Lincoln, 113-121).

On June 13, 1862, Lincoln shared privately with two cabinet members that, “We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued” (Lincoln, 124). Lincoln was still reflecting on the idea of total emancipation. At this point, Lincoln’s plan with slaves was still colonization. The idea of not increasing the amount of freed black people in the States by shipping them back to Africa sounds immoral by today’s standards. Lincoln saw it as the best option (Lincoln, 125). Lincoln decided in private that emancipation would save the Union.

Lincoln stated his goal was to save the union. In a letter sent to Horace Greenly, Lincoln stated, “My paramount object in the struggle is to save the union . . . and if I could do this by freeing all the slaves I would do it” (Lincoln, 130). This letter was published in newspapers throughout the North and hinted that Lincoln had made a decision on what to do to save the Union. At the end of that letter, he also stated that it is his personal wish that all men could be free (Lincoln, 129-130). The Union Army was doing well on the battlefield and this success gave Lincoln more support to announce emancipation.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law. This was a huge step in Lincoln’s moral agenda. As he signed the document, he said, “I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do signing this paper” (Lincoln, 140). The Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves in Confederate states where Lincoln claimed he had the constitutional authority to do so because of the Confederacy’s succession from the Union. The Emancipation Proclamation began the process to end slavery.

Months after Lincoln’s victory for a second term, and after great success on the battlefield, he proposed a 13th Amendment to Congress that would abolish slavery throughout the United States. Lincoln signed this resolution to be presented to Congress calling it, “A great moral victory” (Lincoln, 196). Lincoln favored a plan that would compensate slave states a total of 400 million dollars. There were many reasons Lincoln wanted to do this; the plan showed Lincoln’s continued ethic of respect for others, even slave masters and their property rights. This proposal, however, never made it to Congress (Lincoln 197-198). Sadly, Lincoln did not see the fruits of his entire presidency’s labor. He was assassinated on April 14th, 1865 The 13th Amendment was signed into law on December 18th, 1865

Lady Elizabeth Greenly

Elizabeth Brown Greenly was born at Titley Court, Herefordshire, on the 27th November, 1771, the only child of William Greenly and his wife Elizabeth (née Brown). They had a town house in Abergavenny and property near Cwmdu, Breconshire, as well as the estate in Herefordshire. William Greenly was said to have been 'an excellent scholar and antiquary, and a man of great goodness of heart and simple manners'.

Elizabeth, usually known as Eliza, was said to be 'a person of so much real merit, & of such superior & general cultivation of mind, that her superiority to the contemporary and surrounding society was too self-evident not to excite astonishment' ... She was an ardent supporter of the Welsh causes of the day and was one of the first to support Iolo Morganwg (Edward Williams 1747 - 1826) beginning her patronage in 1806, and continuing for the rest of his life. Lady Llanofer's mother (Georgina Mary Ann Waddington, née Port) was the same age as Eliza and the two were close friends. A frequent visitor to Llanofer, Eliza no doubt encouraged the interest of young Augusta Waddington (later Lady Llanofer) in these matters.

She had a good voice and on her visits to the Waddington family she would entertain them with her singing - usually the old Welsh folk songs of which she was very fond. According to Frances (Lady Llanofer's sister, who later became Baroness Bunsen) Eliza's voice 'was not of superior quality, but her taste was refined, & she had an admirable collection of songs'. Perhaps it was this introduction to the old tunes while she was young that made Augusta Waddington so enthusiastic about Welsh music throughout her life.

Eliza was good natured and attractive and 'considered clever, of a religious nature and inclined to literary pursuits'. She had a number of suitors but, according to Baroness Bunsen, any man who might have been a suitable husband for Eliza, and acceptable to her, was 'frightened off from prosecution of his suit, by the ever-increasing demands made upon him as conditions of consent to marriage, by the Mother & Grandmother' ... The Grandmother, Mary Brown, was head of the family, 'adding whalebone to Mrs. Greenly's buckram, in all family concerns', as Baroness Bunsen remarked in her Reminiscences written in 1874.

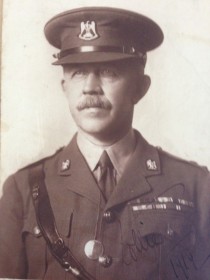

The man Eliza eventually married, in 1811, was Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin, a man more than ten years her senior, and an erratic seafarer who suffered from gout. He took the name Greenly on marrying Eliza, heiress to a considerable fortune. Eliza was said to have 'some eccentric habits (such as getting up in the middle of the night to write sermons)' and maybe this contibuted to his less than satisfactory behaviour towards her following their marriage. Her behaviour appears to have been without fault, but after the first year of marriage he went to visit friends and stayed away for seven years!

He communicated with her only rarely, and on the few occasions he did return, it appears that he was very disagreeable. Eliza once wrote, 'One moment he makes me love him, at another his unfeeling letters and actions completely repel me'. Sir Isaac's relatives and friends sympathised with the long-suffering Lady Coffin Greenly.

Eventually Sir Isaac dropped the name Greenly, and Lady Greenly stopped using the name Coffin.

In 1823 Augusta Waddington married Benjamin Hall III and they lived in a rented house in Herefordshire where they were neighbours of Lady Greenly. She no doubt continued to share her enthusiasm for the Welsh language, which she spoke extremely well, with the young Mrs. Hall. '... contrary to the general belief today, there was still a great deal of Welsh spoken in Herefordshire at the period'. In spite of the age difference between the two woman, Lady Greenly and Augusta Hall were great friends, and Eliza Greenly became one of the god-parents of Augusta and Benjamin's first child, Augusta Charlotte Elizabeth (later Mrs. Herbert).

Lady Greenly, always an ardent supporter of the Welsh causes of the day, attended every eisteddfod in south-east Wales. In 1833 she wrote to her cousin Louisa Hastings :-

'To all, who from ignorance or prejudice oppose these national meetings, [i.e. eisteddfodau] let it be said that whatever preserves nationality - that love for the language, customs, habits and appearance of our forefathers which has most commonly a strong hold on the uncorrupted mind, ought to be encouraged, for it cannot be doubted that the prevalence of such feelings is the safeguard of a people.'

Mrs. Hall (later Lady Llanofer) won the prize for the best essay on the advantages of preserving the language and dress of Wales, at the Cardiff Eisteddfod of 1834, but Lady Greenly had also sent in an entry. She used the pseudomyn Llwydlaes, and her entry was complimented for its style and language. Her generous and unassuming nature enabled her to write to her cousin, Louisa Hastings:-

'Mrs. Hall was called upon to receive the Ring from Lord Bute amidst a thunder of applause - she had kept the secret so profoundly that everybody was as much surprised as pleased, and I hope that even I (Llwydlaes) did not envy her success too much' ...

A week later she wrote again to her cousin saying that 'Dear Mrs Waddington ... told me I ought to have had the Ring, for I had no one to assist me in writing the essay which was the spontaneous production of the moment. To this, however, I could not agree, Mrs. Hall took great pains and had opportunities of research which I had not, and deserves a reward for her diligence'.

In 1835 Lady Greenly suffered a slight stroke and this, together with rheumatoid arthritis caused her to be less active. Previously she had been a keen horsewoman, and spent many hours on horseback travelling between Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Glamorganshire, and Breconshire. According to Baroness Bunsen:-

'Miss Greenly & most of her contemporaries relieved themselves from the long tyranny of whalebone by casting off all wholesome ligatures , & for the most part, condensing all visible dress into a riding habit which was rarely taken off ... the riding habit was in her case the more indispensible attire, as trotting many a weary mile was necessary after her Parents settled for good at Titley, to enable her to enjoy any of the society welcome to her ...'

From then until her death in 1839, Lady Greenly was unable to attend the eisteddfodau, although she continued to support and encourage them.

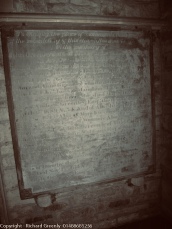

Eliza Greenly died on 29th January 1839 and was buried at St. Peter's Church, Titley, where the following inscription appears on a monument to her memory:

Sacred to the memory of the Lady Elizabeth Brown Coffin GREENLY, only child of the late William GREENLY esq. of Titley Court and of Elizabeth his wife; and wife of Admiral Sir Isaac COFFIN Bart G.C.H. who took the name of GREENLY by letters patent on his marriage.

She was born on the 27th November 1771 and died on the 29th January 1839 aged 67.

This monument is erected by her surviving parent in memory of her virtues and of her talents which she dedicated through life to the cause of religion and morality.

In her character were blended the qualities most loved of God - Piety, Humility and Sincerity joined to a clear understanding and matchless sweetness of disposition.

Her resignation and cheerfulness under severe and protracted trials attested the firmness of her faith in "him who was made perfect through suffering" and inspired the tenderest affection in those around her and the deepest sorrow at her loss.

Her remains rest in the vault underneath the tower erected by herself

at the west end of this church.

Them who sleep in Jesus will God also bring with him.